Oregon’s “Progressive” Income Tax is Among the Country’s Flattest

State tax revenues are bouncing back from the pandemic recession, buoyed by rising wages, thriving financial markets, and nearly $2 trillion in federal aid. Many states are using these surplus revenues to make their tax codes more structurally competitive to lure individuals and businesses. While these reforms come in different shapes and sizes, most governors and lawmakers are turning to targeted incentives or broad overhauls to make their tax codes simpler and more competitive.

Among states either enacting or exploring broad overhauls of their tax systems, the flat tax seems to be making a return to our policy lexicon. Generally speaking, a flat tax’s single low marginal rate is seen as simpler, more competitive, and more likely to maintain stability, providing longer-term certainty for taxpayers. For states looking to redesign their tax systems to lure individuals and investments, adopting a flat tax is certainly one way to make a state stand out on the map.

Oregon is an extreme outlier. Although Oregon boasts a tradition of progressive politics and policy, its tax structure fails to meet some of the basic principles by effectively imposing a high-rate flat tax. At its most basic level, Oregon’s personal income tax has a graduated or progressive marginal rate structure, ranging from 4.75 percent to 9.9 percent. However, the arrangement of those brackets effectively operates as a high-rate flat tax, imposing the second-highest rate of 8.75 percent on anyone with taxable income exceeding a mere $9,200.

| Single Filer | Joint Filer | |

|---|---|---|

| 4.75% | $1-$3,649 | $1-$7,300 |

| 6.75% | $3,650-$9,199 | $7,301-$18,399 |

| 8.75% | $9,200-$124,999 | $18,400-$249,000 |

| 9.9% | Over $125,000 | Over $250,000 |

No other state imposes a hidden high-rate flat tax like Oregon. Six states and Washington, D.C., have marginal tax rates as high or higher than Oregon, but their rates apply at significantly higher starting points. Often regarded as the epicenter of high state taxes, California does not apply its 9.3 percent rate until a taxpayer’s income exceeds $61,214. New York, another notoriously high tax state, does not impose its 9.65 percent rate until a taxpayer’s income surpasses $1 million.

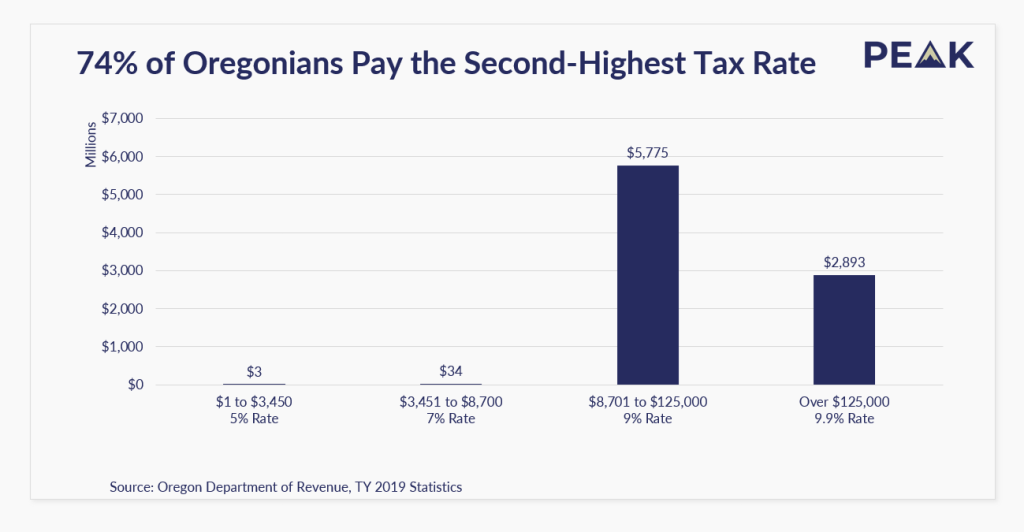

It should be no surprise that Oregon’s second-highest income tax rate raises a tremendous amount of revenue for the state. In 2019, the last year with complete tax return data available, Oregon collected nearly $6 billion from taxpayers paying the second-highest rate. Almost 74 percent of Oregon taxpayers pay the state’s second-highest tax rate of 8.75 percent, making the state’s income tax feel and function like a flat tax, without any of the welcome benefits of a flat tax. The graph below illustrates the state’s tax collections per income tax bracket for the 2019 tax year. It should be noted the legislature trimmed the tax rates slightly for tax years beginning on or after January 1, 2020, to account for potential cost increases from the corporate activity tax. Despite the somewhat lower rates, it is fair to assume the 2019 data is analogous to future tax years.

Oregon adjusts all but its top marginal income tax rate to inflation each year, but the overall bracket structure renders these adjustments, at best, perfunctory. This is because the second-highest rate bracket applies to a range of income spanning the vast majority of taxpayers. If anything, Oregon’s refusal to index the top marginal rate to inflation harms taxpayers because high inflation and wage increases make it easier for an individual to cross the threshold to the highest rate.

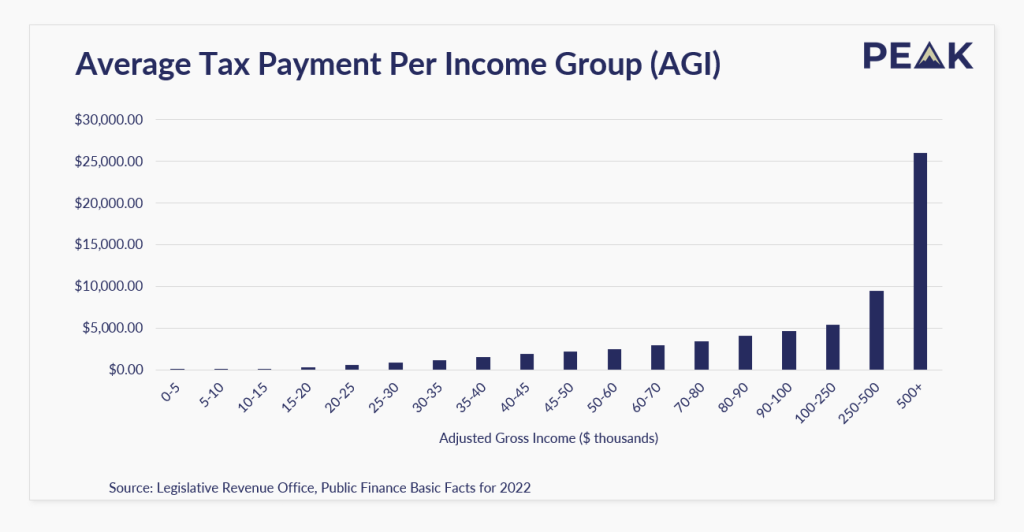

Some local groups, like the Oregon Center for Public Policy, often assert that Oregon needs to raise its top marginal income tax rate to make the tax structure fairer. That conclusion entirely misses the problem. Oregon’s tax structure is progressive in that the wealthiest taxpayers bear a greater share of the tax burden. The problem is that the overall rate structure is significantly less progressive for low-, middle-, and upper-middle-income Oregonians by taxing them at the same high rate. Raising the top rate would do nothing to alleviate the burdens of those in the second-highest bracket—it is simply a money grab. Instead, Oregon should look at reforming its second-highest rate by either reducing the overall rate or breaking the bracket into multiple rates.

More importantly, Oregon could reform its rate structure to address these issues without raising taxes or cutting budgets. The state’s third-largest tax expenditure, the limited federal income tax subtraction (i.e., deduction), is ripe for reform. Oregon is one of only three states to allow taxpayers to deduct some of their federal tax payments from their state taxes. Although the policy’s purpose is well-intentioned, it results in a complicated and counterintuitive mechanism that raises or lowers state tax liabilities in response to federal tax law changes. If Oregon repealed the policy and used those revenues to offset structural rate reductions, lawmakers could simultaneously reduce the tax burden for many Oregonians while providing more fiscal certainty for the state budget.

The pandemic has fundamentally enhanced an individual’s geographic mobility and, more importantly, the freedom to live and work in a community that is most economical. If Oregon wants to compete with other states and lure people and jobs, reducing the burdens on everyday Oregonians would be a helpful starting point.