Restoring & Enhancing Oregon's R&D Tax Credit: A Primer

Introduction

Oregon lawmakers are considering proposals to restore and potentially enhance the state's research and development (R&D) tax credit. Until 2018, the state provided a credit of 5 percent of federally qualified research expenditures to corporations, s-corporations, and partnerships, with a cap of $1 million. The tax credit was designed to incentivize businesses to invest in research within the state, fostering innovation and driving economic growth. However, the credit expired in 2018, leaving businesses without this important incentive. Now, lawmakers are exploring ways to bring back the credit to make Oregon more attractive for firms looking to invest. This article will explore the basic mechanics and benefits of restoring and improving the R&D credit.

The Mechanics of the R&D Tax Credit

During the 2017 legislative session, Oregon lawmakers allowed the state's Qualified Research Activities Tax Credit to expire for tax years beginning on or after January 1, 2018. However, the credit still exists in statute. ORS 317.152 provides a credit of five percent of federally qualified research expenditures under Internal Revenue Code (IRC) § 41, up to a maximum annual credit of $1 million per taxpayer. The credit can be used to offset Oregon income tax liability and is available to s-corporations, partnerships, and corporations. If a business has no tax liability to claim the credit against, it can carry the credit forward for up to five years.

The following expenses are generally considered eligible for the federal R&D tax credit:

- Wages and salaries paid to employees for performing research activities. This includes amounts paid for direct supervision, testing, and analysis but not for administrative or support tasks.

- Supplies and materials used or consumed during the research process. This includes raw materials, prototype components, and similar items.

- Contract research expenses paid to third-party contractors for performing research activities on behalf of the business. The expenses must be related to qualified research activities and must be paid to an unrelated party.

- Fees paid for the use of computers, software, or other equipment used in research activities. This includes costs for renting or leasing equipment as well.

- Costs associated with the development of prototypes or models, including design costs, model building costs, and testing expenses.

Let's consider an example as if Oregon's credit was still available. WidgetCo spends $375,000 in qualifying research expenditures, including $200,000 in wages, $50,000 in supplies, $100,000 in contract research expenses to third-party companies, and $25,000 in fees paid for using computers and software, all used for research activities. WidgetCo would multiply its $375,000 in expenses by the tax credit rate of five percent, arriving at $18,750. If the company does not have a sufficient tax liability to claim the full credit, it can carry the credit forward for up to five years.

Perhaps most importantly, the R&D credit is an "incremental credit," meaning that it is based on the increase in research expenditures from the previous year. This requirement is intended to encourage businesses to increase their investments in research and development activities over time, rather than simply maintaining their current spending levels. Unlike some tax incentives that benefit general activity, a firm can only claim the R&D credit if it continually increases its spending each year.

Recent Federal Law Changes for Research Expensing

Another area of tax law that impacts R&D activity is the procedures for when and how a business claims expense deductions to recover the costs of its equipment, machinery, and other assets used for research purposes. IRC § 174 details these rules. Until recently, a business could choose to either immediately deduct ("expense") research and experimental expenditures in the current year or to capitalize them and amortize them over a period of time. In 2017, as part of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, Congress eliminated the option for a business to immediately recover the costs of these expenses, requiring them to amortize these expenses over five years. That change went into effect for tax years beginning on or after January 1, 2022. In effect, the tax change penalizes companies for conducting research and experimentation.

States have the opportunity to decouple from IRC § 174 to make their tax codes more competitive and stand out in the crowded field of states seeking to lure investments in research activities. If a state were to decouple from these requirements, instead deferring to the previous treatment allowing a business to immediately expense its research costs, it can encourage firms to invest in areas crucial to the state's long-term growth and prosperity.

Economic Benefits of Research Incentives

Research incentives are highly effective at luring and sustaining direct investments in people, communities, and the future of our economy. These investments most often lead to additional innovations, including first-generation manufacturing and further product and process development. The benefits from research tax credits are not limited to the companies and sectors where these investments occur but also industries that use those innovations.

While companies need to research and innovate to remain competitive in their respective markets, many operate in more than one state and have choices when deciding where to locate those activities. States that offer R&D tax credits are better prepared to attract these investments than those that do not. By offering these incentives, states can create a more favorable business environment for R&D and innovation, leading to job creation, economic growth, and increased competitiveness. Furthermore, the availability of a R&D tax credit signals to companies that a state is committed to supporting innovation and technology development. This commitment can be essential in attracting companies that value innovation.

The economic growth induced by research credits, such as high-wage jobs, effectively pays for the costs of the credit, making it one of the best “investments” a government can make in its economy. The Connecticut General Assembly explored the effects of its R&D credit in 2015, finding the state earns between $1.24 and $2.36 in net revenue for every dollar claimed from its credit. It is no wonder why states compete so aggressively for these investments.

Comparative Analysis of State R&D Credits

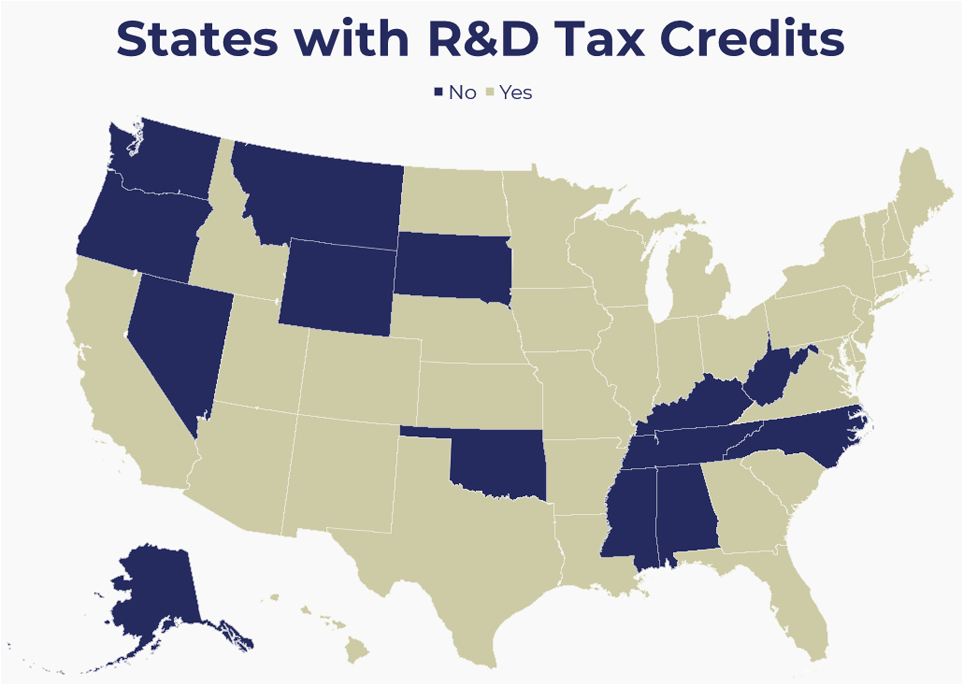

Despite the clear benefits of R&D tax credits, 13 states do not currently offer them, which puts them at a competitive disadvantage when attracting new investments in jobs and capital projects. Notably, many states without a tax credit engage in other ways of luring these activities. For example, North Carolina allowed its credit to expire but is phasing out its corporate income tax. Similarly, Washington state lawmakers allowed their credit to expire but, instead, offer preferential tax rates to many firms in research-intensive sectors. Among states with relatively strong R&D clusters, Oregon is the only state without a policy tool to spur private-sector research, putting the state at a competitive disadvantage in attracting investments to benefit the local economy.

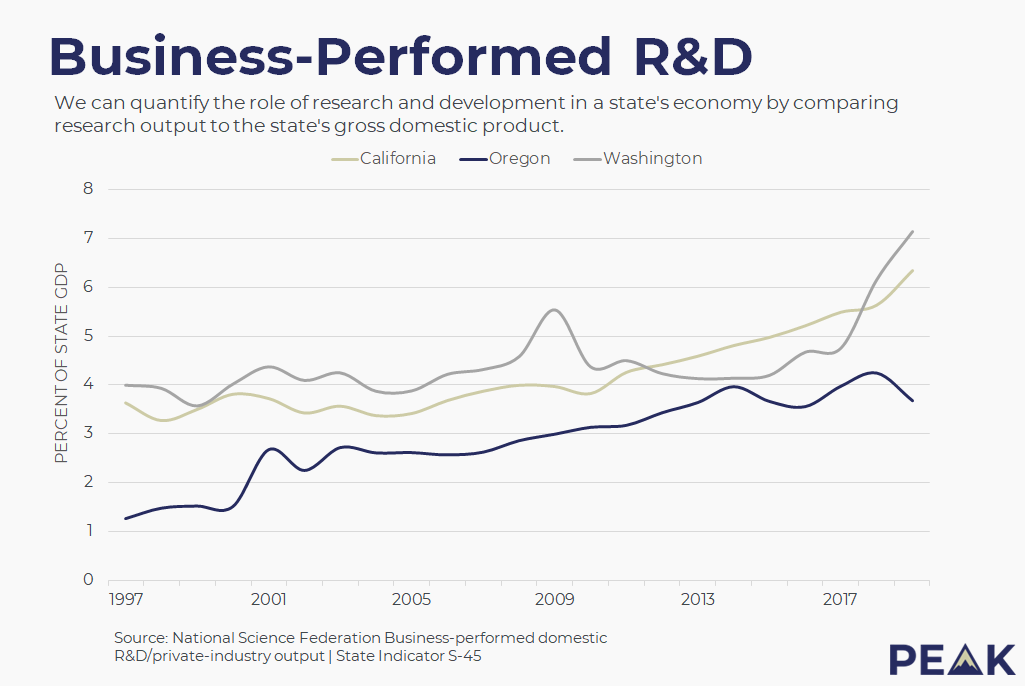

According to the National Science Foundation (NSF), Oregon experienced a 10 percent decline in business-performed research activities in the year after the state allowed its R&D credit to expire. The impact of this decline was felt across the state, with fewer research jobs and reduced economic growth. Preliminary data for 2020 indicate an increase; however, the increase is likely attributable to the infusion of research investments in medical and biotech sectors to aid the government's response to the coronavirus pandemic.

The NSF data from 2019 reveals a worrying trend for Oregon's economy. The loss of R&D investment leads to fewer jobs, reduced economic growth, and lower tax revenue for the state. It is essential to note the decline in R&D spending is not limited to one industry but cuts across multiple sectors, including high-tech, biotech, and manufacturing.

Lawmakers Should Use Dynamic Scoring to Understand Benefits of R&D

Oregon lawmakers are actively exploring comprehensive tools to lure investments from the semiconductor industry as the federal government begins accepting applications for the CHIPS & Science Act. As Oregon competes for these investments, it is important to remember the state's opportunity for growth is not limited to this industry alone. To fully capitalize on this generational opportunity, Oregon should use this effort to support innovation and growth across a wide range of sectors.

As part of these discussions, Oregon is considering several proposals to restore and enhance its R&D credit. If done correctly, the state would send a clear message to businesses that it is committed to supporting innovation and economic growth. This would help attract new business activity to the state and encourage existing businesses to expand and boost overall growth.

Further, Oregon has a suite of tools to evaluate the effectiveness of these proposals. In 1999, Oregon became one of the first states to develop and utilize a state-level dynamic scoring model. The Oregon Tax Incidence Model (OTIM) helps lawmakers understand the dynamic and distributional impacts of state tax law changes. Over the years, the legislature has relied on OTIM to understand the real-world implications of significant tax reform proposals, allowing lawmakers to make informed decisions about tax cuts and increases.

While a static revenue estimate of the R&D credit may show a revenue loss, the estimate does not consider the downstream economic benefits from increased investment in the state. Dynamic revenue scoring is crucial for evaluating the value of tax incentives, which, by definition, are intended to nudge certain behaviors in the economy. With the right incentives, businesses will increase their local research investments, resulting in high-paying jobs, improvements in productivity, and, consequentially, more tax revenues collected from those activities.

Opposition to Oregon's R&D Credit is Misguided

While some progressive tax advocacy groups, like the Oregon Center for Public Policy, oppose efforts to restore and enhance the state's R&D credit, their position is misguided. The chief concern raised by these groups is that tax incentives consume resources that could otherwise support important state programs. While true on a static revenue loss basis, the real-world application of these programs proves otherwise.

When a business invests in research, it creates new jobs, increases purchases of goods and services, and generates additional economic activity. The increase in economic activity from these investments ultimately broadens the tax base and raises the amount of taxes the government collects. Opposing the R&D credit on the basis that it costs resources is shortsighted because the gains from the economic activity provide additional revenues for the government to deploy to address the state's spending needs.

Conclusion

The decline in R&D spending in Oregon is a concerning trend for the state's economy and the ability of its business community to remain competitive in the global marketplace. While the CHIPS Act presents a generational opportunity for Oregon's semiconductor industry, the state is also presented with a historic opportunity to fundamentally shift the state’s business image and signal it is committed to supporting innovation and prosperity. If Oregon lawmakers seek to restore and enhance the R&D credit, they should do so in a way that benefits all sectors.